The South Solitary Island Lighthouse Optic (SSILO) is the largest and one of the most significant items in the collection of Coffs Harbour Regional Museum. In early 2020, Coffs Harbour City Council commissioned a Management Plan to inform how best to preserve, protect and promote the SSILO into the future. Undertaken by International Conservation Services and Story Inc., the Management Plan provided an opportunity to dive deeply into the fascinating history and exciting future of this most special object. This blogpost shares some of the information that came to light.

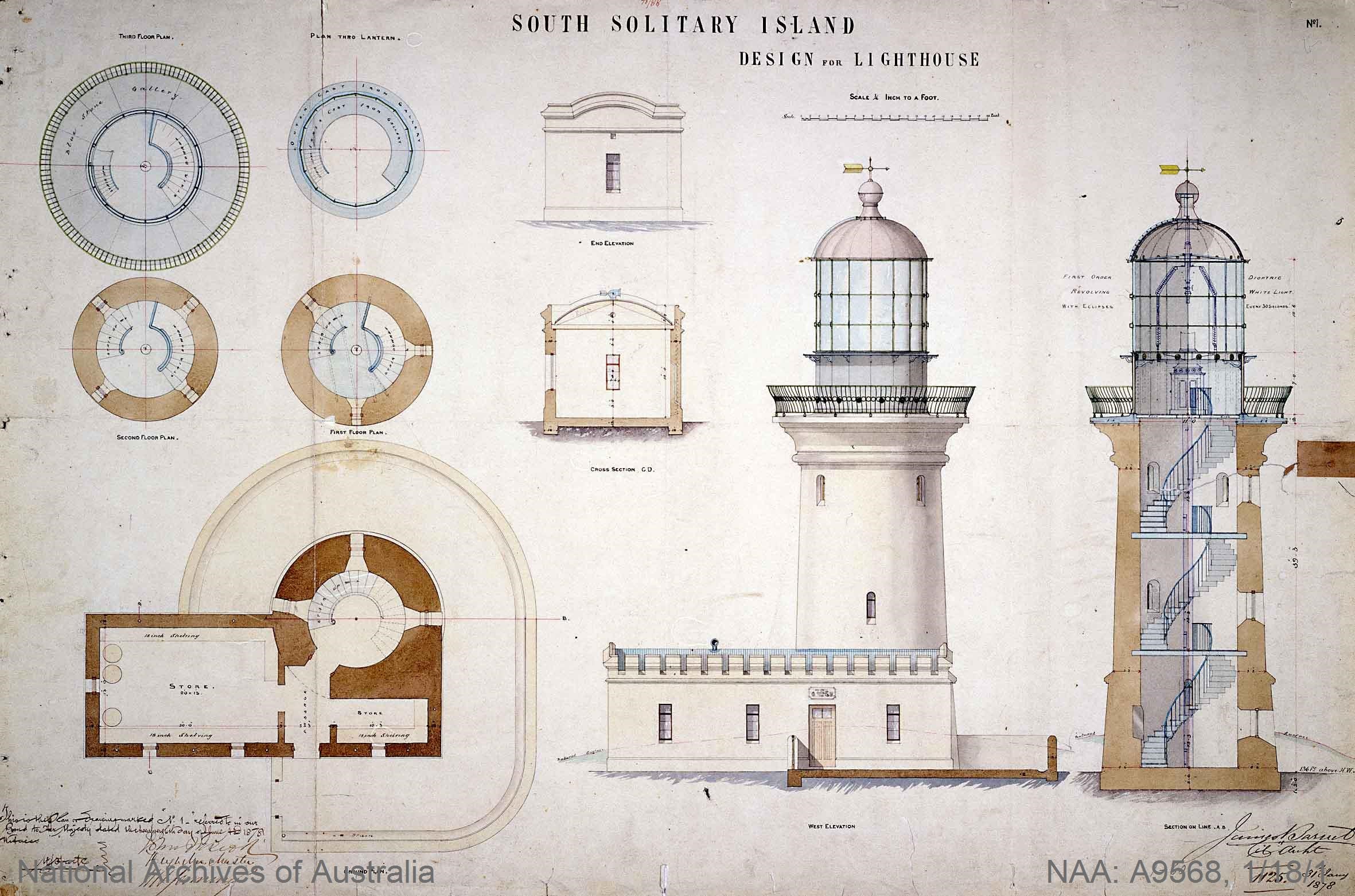

The South Solitary Island lighthouse was a critical factor in the early development of our region in both economic and social terms, allowing the expansion of trade, industry and employment opportunities that would have otherwise been restricted by the treacherous maritime environment. The need for a lighthouse at South Solitary Island was raised as early as 1856; actual construction commenced in July 1878 and took 20 months. This latter part of the 19th century was a peak period of lighthouse construction and South Solitary Island was an important link in the highway of coastal lights along the New South Wales coast.

The First Order Lens, or optic, was supplied by the famous British firm Chance Brothers and was installed in the lighthouse in 1879. Chance Brothers was a leading glass manufacturer in Birmingham established in 1824, responsible for the Crystal Palace in 1851 and the glass faces for the Westminster Clock Tower/Big Ben. They manufactured lights and apparatus for hundreds of lighthouses across the world. The glass manufacturing process required a series of complex machining and polishing processes. Unfortunately, Chance Brothers’ specialist machines were destroyed by bombing in the Second World War and replacement glass for lighthouse optics can no longer be manufactured anywhere in the world.

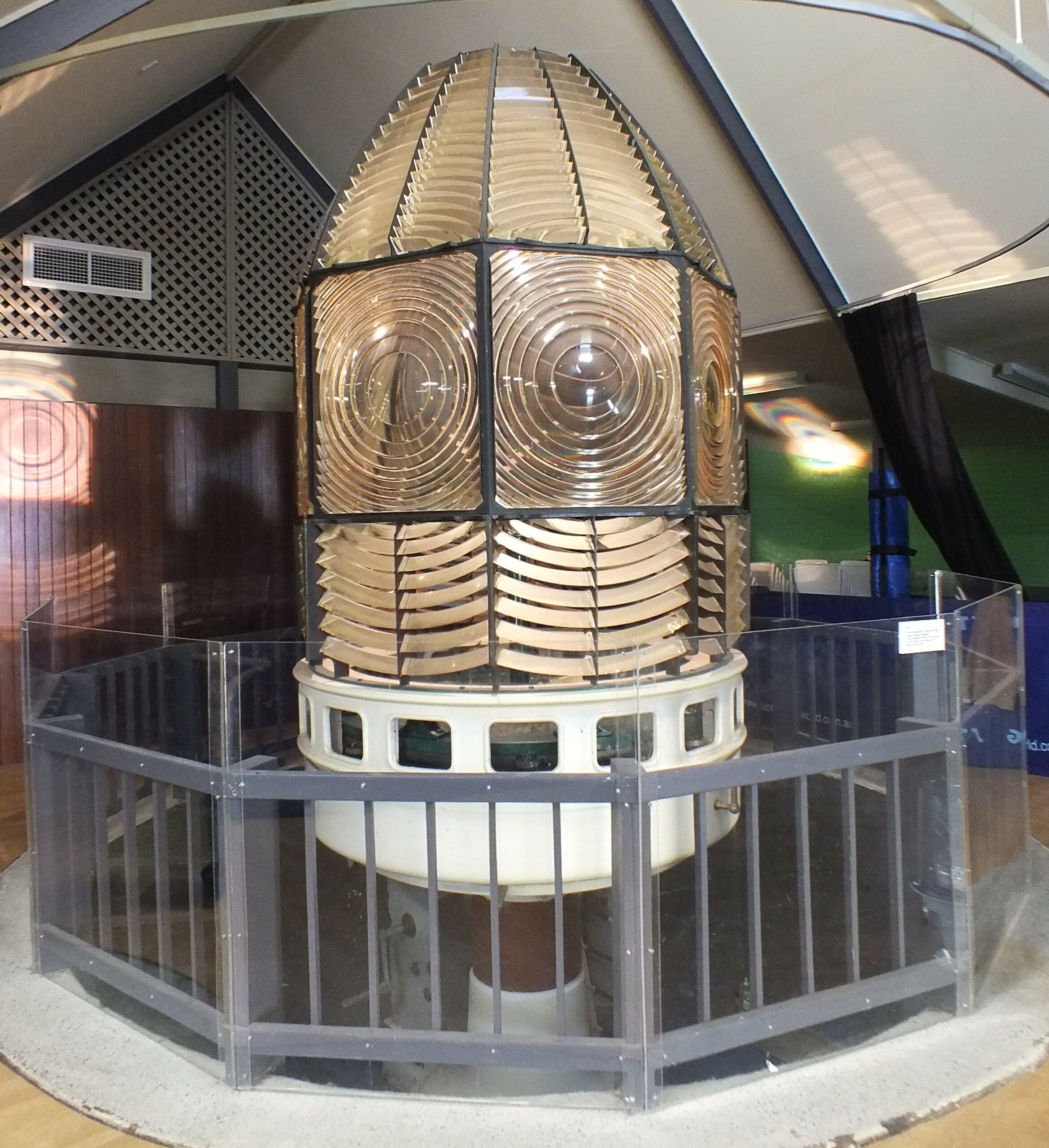

The SSILO was the first in New South Wales to operate on kerosene instead of the widely used colza oil, and continued to provide light from kerosene later than any other New South Wales lighthouse, as it was not automated until 1975. Its design was developed from the work of Augustin-Jean Fresnel, a French physicist who pioneered optics, particularly polarised light. He established the use of compound lenses instead of mirrors for lighthouses. The SSILO Fresnel lens is a First Order (the most powerful type) dioptric lens. It has eight panels with prisms of flint glass (often called lead crystal) and each panel has 127 pieces in a gun metal frame. The lens sits on a cast iron pedestal and was set in a bath of mercury to provide frictionless rotation.

When the SSILO technology became redundant, Coffs Harbour City Council took over responsibility for the optic from the Federal Government and it was removed from the lighthouse in two stages between 1975 and 1977, with assistance from a RAAF Chinook helicopter. Vigorous debate took place locally and various plans were put forward. Should it be in the CBD, or by the sea? In a replica lighthouse, a park or a museum? Ultimately, it was installed in 1980 in Coffs’ first museum, then located at 189B Harbour Drive and operated by the Historical Society. Council funded the works – a specially-designed sunken floor area was constructed and engineering staff spent many months sand blasting the frame, cleaning the glass and working out how to fit the SSILO all back together again before carefully craning it into the building before the roof was completed. The museum has since re-located to 215A Harbour Drive due to flooding risk and the original building is hired to local table tennis clubs. A perspex shield has been installed to protect the SSILO and it can be viewed by appointment.

As this short history highlights, key to any consideration of the future location of the SSILO is an understanding of the process of disassembly and reassembly of this priceless glass object. There are two schools of thought on this, one being that it is a highly complex and expensive exercise that should only be undertaken when the final and permanent location of the optic is resolved, as it is likely that it will be too risky and too costly to move again. Costs of $300-$400,000 have been mentioned! This view has been reinforced by the images of the Chinook helicopter removing the SSILO from the island and the knowledge that the pedestal was lifted into its current location by a crane through the roof of the former museum.

The other school of thought is that the disassembly of the optic is a relatively simple process that could be undertaken by a couple of skilled fitters and machinists in a week. Certainly it needs to be remembered that the optic originally came to South Solitary Island as a series of parts in crates, and if it was feasible to haul these to the top of a lighthouse in such a remote and inaccessible location and install it there with 19th century equipment, it must be feasible to take it apart and relocate it in Coffs Harbour in the 21st century! Happily, it is the consultants’ view that disassembly and reassembly of the optic can be undertaken relatively simply. The SSILO can be dismantled into small enough component parts and brought out of the former museum through the doors, thus not necessitating the removal of the roof. Another mystery that was solved during the Management Plan was whether the SSILO still contained mercury. Although the fate of the mercury is unknown, we can confirm that there is no longer any mercury in the cast iron “bath” in the pedestal; it now contains lubricating oil.

The consultants also gave serious consideration to the question of the future location of the SSILO:

“Visiting SSILO allowed (us) to see its huge value to the Coffs Harbour community, both as an object of beauty and as an historical and technological wonder. It is fully understandable why the Council fought so hard to retain ownership of it at the time of its decommissioning from South Solitary Island, and the community pride it has engendered over the 45 years since. More broadly there is a wider national interest from both the maritime history and heritage sectors. It is therefore clear that SSILO’s current location within the non-operational museum should change to overcome the lack of access for the local community and tourists. The opportunity of this project is to create a reimagining and contextualization that allows SSILO to be both fully interpreted and fully appreciated.”

Predictably, there are just as many options and opinions about the future of the SSILO today as there was back in the 1970s when it first came ashore. The consultants considered a number of these, including: continuation of the status quo, 189B Harbour Drive; placement into long term storage; placement into museum storage with guided tours; relocation to the new Cultural and Civic Space; and relocation to a revitalised Jetty Foreshores.

They sought the views of stakeholders including Friends of South Solitary Island Lighthouse (FOSSIL) and the Australian Maritime Authority (AMSA). FOSSIL members contributed many positive ideas and were open to various possibilities but their overall message was clear: SSILO belongs by the sea. On this point the consultants agree, stating that “the optimum position for the long term location of SSILO should be adjacent to the harbour within sight of the sea.

SSILO’s future became clearer in early May 2020 just before the Management Plan was completed when the NSW Government announced Stage 3 of the Coffs Harbour Jetty Foreshore Precinct master plan project. It will surely be the “jewel in the crown” of our beautiful harbour precinct.

Jo Besley, Museum and Gallery Curator

South Solitary Island: Design for Lighthouse, James Barnet – NSW Colonial Architect, 1878. Courtesy of National Archives of Australia, A9568, 1/18/1

South Solitary Island: Design for Lighthouse, James Barnet – NSW Colonial Architect, 1878. Courtesy of National Archives of Australia, A9568, 1/18/1

Many more images of the Lighthouse and its optic over their lifetime are available in Coffs Collections.