In the somewhat daunting queue of items awaiting our attention to be added to the Museum’s collection, we found a small set of interesting photos we had never seen before.

Unfortunately, the photos did not have any indication of who donated them or when. The Museum is often a ‘victim’ of what might be termed ‘a hit and run’. Items which seem to have historical relevance are left at the Museum door or the Library desk without contact information or details about why someone considered them to be important enough to leave with us. The queue grows longer while we try to establish the significance of items and spend extra time tracking their historical value.

Items without context, dropped off or poorly scanned and emailed in, are less interesting all round. Should we spend the time investigating them, or only choose items for the collection which have all relevant information attached? How do we share the story around orphaned items with the community we serve?

Fortunately, in the case of this small set of photographs, there were a couple of accompanying articles. Unfortunately, the sources and dates of some of those articles were cut off; another frequent act which slows down our research. Should we spend the time to find out more at the expense of other more deserving items?

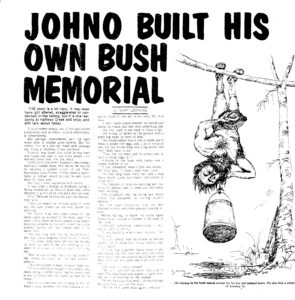

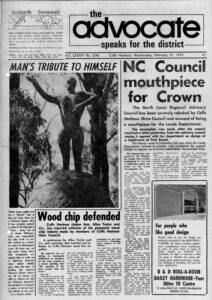

Jonas Zilinskas was a Lithuanian-born acrobat who came to Australia as a Displaced Person after the end of World War II. In the early 1950s, he performed in Wirths’ Circus, gripping a metal bar inside his mouth for a trapezist to swing from. During a performance the trapezist moved the wrong way, pulling the bar and several teeth from Zilinskas’ mouth. They both took a career break.

His second job was in the Newfoundland State Forest [Yuraygir National Park] as a sleeper cutter. He lived and worked in this forest with one colleague, both dressed only in hat and boots. He invented a swingcut saw for them to use together. Before his departure two years later, Zilinskas constructed a sculpture of himself with materials to hand including keys, beer bottles, timber and concrete.

Zilinskas was able to resume his celebrated circus career with Ashton’s and other circuses.

We don’t know exactly when the photographs of Jonas’ sculpture were taken, or who the photographer was, but the story they represented was extraordinary. Zilinskas made an impact. His contribution to our community and the broader Australian story was indeed noteworthy.

In the absence of complete supporting information being provided by potential museum donors, we do our best, within limited timeframes, to establish the importance of any item. Meanwhile, the queue of unidentified items grows longer. One day, we will be able to find the right home for each of them. It’s a temporal balancing act.