The current Coronavirus outbreak (COVID19)[1] has certainly aroused fears of a possible global pandemic in 2020 and the reactions of all levels of Australian Government: Federal, State and local bodies have some interesting parallels to the responses made by the same legislative groups back in 1919. Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo districts underwent a level of restrictions unheard of to minimise the possible outbreak of the influenza in the period from April 1 to September, 1919. There have been some successful initiatives adopted by current authorities as a result of the actions taken by the Australian Government to reduce the morbidity rates of the Spanish Flu in 1919; including compulsory notification, nursing and medical assistance, hospital accommodation, extensive use of vaccination, restrictions on travel and assembly (including the closure of schools and churches), and the wearing of masks at certain periods.

Distant view of a temporary isolation camp set up for interstate visitors at Jubilee Oval, Adelaide during the influenza outbreak of 1919. Picture Courtesy of State Library of South Australia. PRG 280/1/9/57

The Spanish Flu is a little of a misnomer as it was associated with the King of Spain catching influenza in 1918 but he managed to survive the illness. Yet the truth is more intertwined with the fortunes of military activities and censorship during World War One of the combating Allied and German forces in the period of 1918, where the outcome of the war was still very much in the balance. Indeed, General Foch, the French General and Commander of the Allied forces, conceded that in May 1918 he had real fears of the German Ludendorff Offensive being successful leading to a decisive victory for the Germans. Likewise, the British Cabinet discussed on June 5, 1918 the possibility of evacuating the entire British Expeditionary force from the Continent[2]. Interestingly, the pneumonic influenza may have been a decisive factor in the demise of German troops. By July 1918, almost half a million German troops had contracted the first wave of the so called Spanish Flu. As well as this misfortune, 400,000 German citizens had died of the disease in 1918 on the Home front sealing the fate of the outcome of the war for Germany combined with the Allied Naval Blockade and civil unrest.[3] Elsewhere, the Spanish Flu had well and truly affected Allied troops.

Sister Anne Donnell an Australian field nurse on the Western Front, contracted the same influenza as early as in early March 1918 but recovered. She believed the flu originated amongst the troops around Etaples in France.[4]

Whatever the origin of the Spanish Flu, the mass return home of armed forces globally led to a greater spread of the disease and misery just after the cessation of the war. Figures vary greatly but most sources acknowledge at least 40 million to possibly 100 million people died during the period 1918-1919. Far more fatalities than World War One of around 18 million people soldiers and civilians combined.

Soldiers returning to Australia and particularly men from Coffs Harbour were looking forward to welcome home parades and ceremonies on their homecoming. It was not to be for many for some time.

The Diggers Ball, Coffs Harbour, 3 September 1919. Front row: (from the left) Beatrice Matten, Dick Gailer, unknown, unknown, ? Worland, Mary Dunlop, Tommy Dent, Joe Cavanagh, Alf Dodd, ‘Nugget’ Worland, Billy Kay. Second row: 6th from left Jim Gailer, 8th from left Jack Knight. Third row (only two people in the row) Billy Sutton on far right. Fourth row: 6th on left Col Buchanan. Back row: Captain Seymour 2nd from the right. Courtesy Picture Coffs Harbour Mus 07-1624. Note the date of the image 3.9.1919

The Diggers Ball, Coffs Harbour, 3 September 1919. Front row: (from the left) Beatrice Matten, Dick Gailer, unknown, unknown, ? Worland, Mary Dunlop, Tommy Dent, Joe Cavanagh, Alf Dodd, ‘Nugget’ Worland, Billy Kay. Second row: 6th from left Jim Gailer, 8th from left Jack Knight. Third row (only two people in the row) Billy Sutton on far right. Fourth row: 6th on left Col Buchanan. Back row: Captain Seymour 2nd from the right. Courtesy Picture Coffs Harbour Mus 07-1624. Note the date of the image 3.9.1919

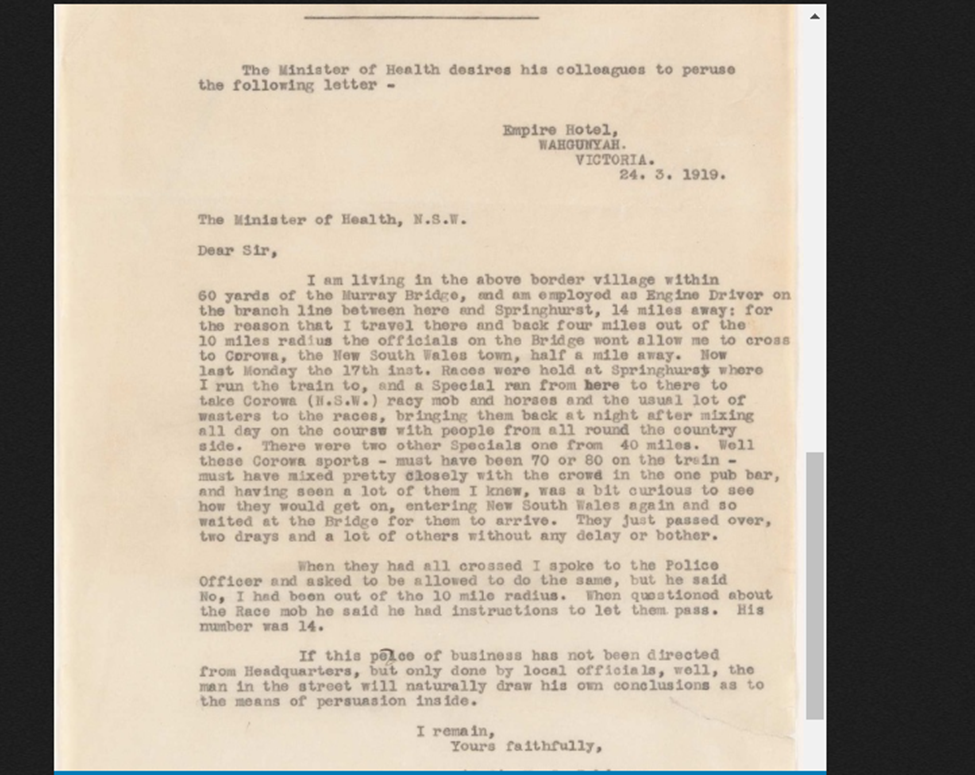

To give some picture of the spread of the disease originating from Victoria towards New South Wales in 1919, a letter addressed to the NSW Health Minister from an engine driver [5] highlighted the problems of enforcing regulations with ex Servicemen who happened to attend the races in Corowa. Reference to them as “wasters” was a peculiar term describing the quarantine breakers.

Courtesy of State of New South Wales through the State Archives and Records Authority of NSW 2016

By January 27, 1919 the Spanish Flu had reached NSW. By the time the disease was officially declared over in September some 6,387 people died in New South Wales, infecting as many as 290,000 in Metropolitan Sydney alone.[6] In terms of loss of life, the ‘outbreak’ first wave of the disease was “comparatively mild” when contrasted with the second and third ‘high-mortality’ waves in 1919. Up until the middle of March 1919, only fifty people had died across NSW, while the second wave killed 1,542, and the third 4,302, with the peak occurring between the weeks ending 24 June and 8 July:

- (Outbreak wave) 27/1/1919 – 18/3/1919

- (High mortality wave) 19/3/1919 – 27/5/1919

- (Highest mortality wave) 28/5/1919 – 30/9/1919

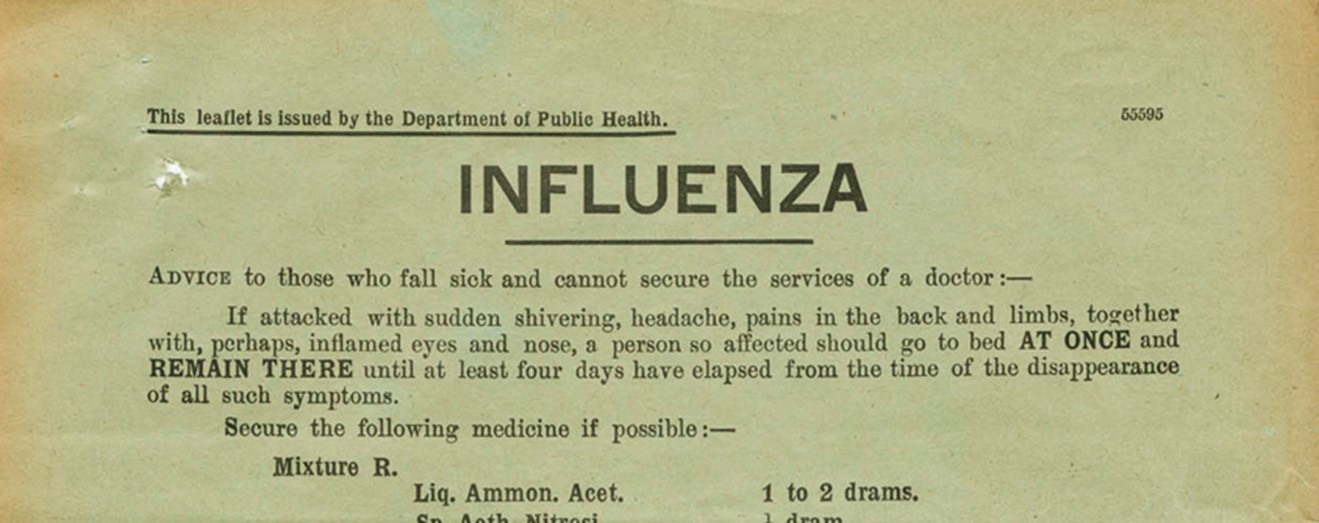

Influenza leaflet, Department of Public Health, April 1919. From: NRS 905, [5/8097], 19/57573

Courtesy of State of New South Wales through the State Archives and Records Authority of NSW 2016

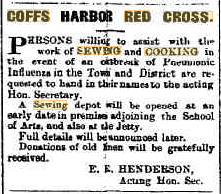

What was unusual about the death rates was the group of males aged between 20 and 39 years accounted for half of the deaths in this period. [7] The NSW Government acted quickly with state wide inoculations and quarantine periods for those people affected. People in Coffs Harbour reacted quickly to the news of the Spanish Flu. Organisations such as the Red Cross started preparations for quarantining people suffering the disease at the Coffs Harbour Showground but desperately needed volunteers. What is interesting to compare were the isolation periods of four days for this pandemic recommended by the Department of Health in NSW compared to the 14 days recommended for the current COVID19 virus in 2020.

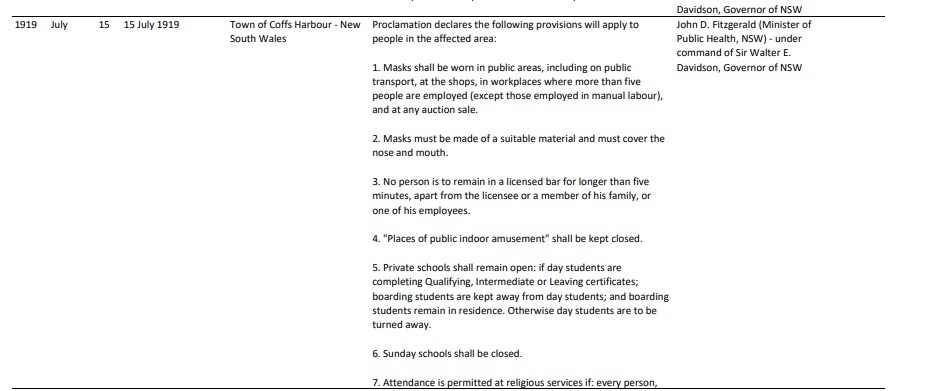

https://www.rahs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Flu-Pandemic-proclamation-timeline-.pdf page41

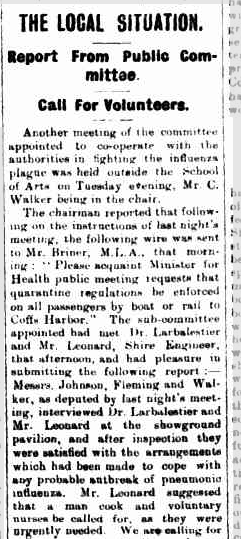

Coffs Harbour Advocate Wednesday April 9, 1919, P.3. Retrieved from Trove.

Coffs Harbour Advocate Wednesday April 5, 1919, P. 2. Retrieved from Trove.

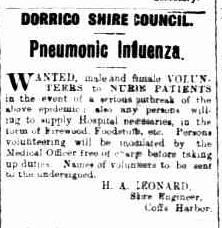

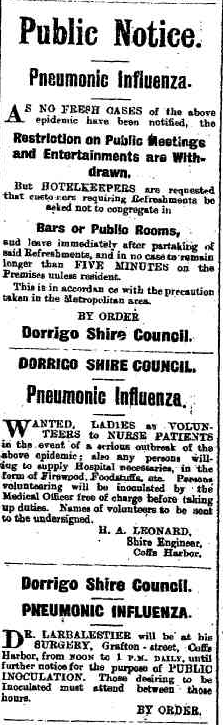

Likewise, in Dorrigo local government regulations were quickly enforced. Drinking in hotels, local social groups and even church attendance were affected.

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate Wednesday April 2, 1919, P.3, Retrieved from Trove.

Public association of any kind was restricted. Imagine a publican enforcing the five minute rule with serving drinks and asking patrons to move along!

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate April 23, 1919, P.3. Retrieved from Trove.

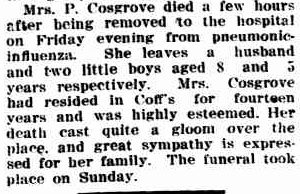

In Australia, while the estimated death toll of 15,000 people was still high, it was less than a quarter of the country’s 62,000 death toll from the First World War. Australia’s death rate of 2.7 per 1000 of population was one of the lowest recorded of any country during the pandemic. In Coffs Harbour, so successful were the prevention measures of quarantine, inoculations and wearing of face masks that only a couple of residents succumbed to the disease. It did affect emotionally the community when death came, as outlined in the newspaper announcement of Mrs Cosgrove in 1919:

The Don Dorrigo Gazette and Guy Fawkes Advocate Wednesday 30th July 1919, P.3. Retrieved from Trove.

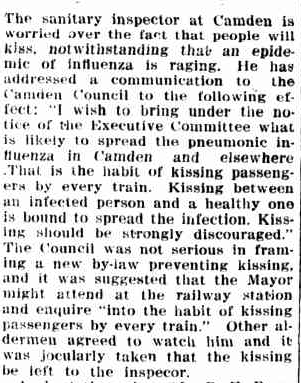

In effect, the death toll was far greater in 1919 than the COVID19 virus in 2020, yet the hysteria and misinformation of the contagiousness of the disease and the protective measures to prevent falling ill bear an interesting comparison. Perhaps the more contagious the disease became during this time, the more anxious were people to minimise the spread of the Flu. Even the morals and health of train passengers, through constant kissing of one another, was a subject of debate at a Camden Council meeting.

The Don Dorrigo Gazette and Guy Fawkes Advocate Wednesday 28th May, 1919, P.4. Retrieved from Trove.

Rhonda Dahlen recorded her grandfather Irvine may have accidentally brought the first case of Spanish Flu to Coffs Harbour after his marriage to his wife Elsie on March 19, 1919 in Sydney. On their return to Coffs Harbour Irvine known as Scob to his family developed flu symptoms of headaches and fever. This was later identified by Dr Larbaleister as a possible case of the Spanish Flu. The Pier Hotel at the Jetty was used to quarantine possible contacts of Irvine Smith whilst he was quarantined at the back of the old police station in a house in North Street. His sister Violet and his mother shared the nursing duties to care for him in his recovery from a mild case of the flu.[8]

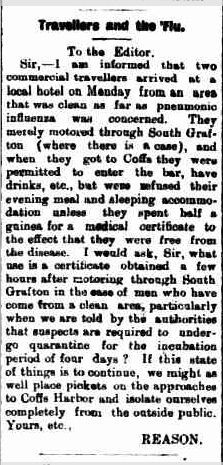

Perusing the local Coffs Advocate during the period of April to September, 1919, there was a steady update of new Spanish Flu outbreaks and deaths occurring in Sydney in virtually every edition, constantly reinforcing the perception that the danger was ever present in the minds of the citizens of Coffs Harbour. This vigilance can be seen expressed in a few letters to the Coffs Harbour Advocate newspaper whenever newcomers to town managed to obtain free passage from infected regions. The following letter is a particularly good example of xenophobia of people living directly to the north of us in South Grafton.

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate Wednesday May 21, 1919, P.2. Retrieved from Trove.

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate Saturday June 28, 1919, P.2. Retrieved from Trove.

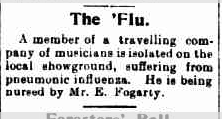

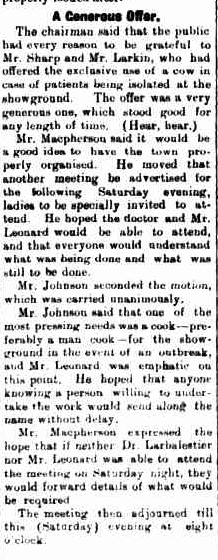

However, not everyone “slipped through the net”, as indicated by the band member being nursed by Mr E. Fogarty. This highlights the importance of selfless volunteering by the people of Coffs Harbour who were a key factor in preventing the spread of the disease by volunteering at the quarantine area at the Coffs Harbour Showground. Additionally, the generous donations of food and linen, as well as a cow for milking, were ways people felt they were being part of the community preventing the spread of the pandemic.

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate Saturday April 5, 1919, P.2. Retrieved from Trove.

The actions of Dr Larbalestier as the town’s physician and Mr Leonard coordinating quarantine and recovery at the Coffs Harbour Showground were important in the low mortality rate. The Showground was used up until August 1919 when the Spanish Flu had run its course in the town. Volunteer nurses were inoculated by Dr Larbalestier, whilst co-ordination of supplies was under the care of Mr Leonard. According to Neil Yeate’s investigation, Mrs Moore from the Red Cross Society and Honorary Secretary helped open up Coffs Harbour Primary School as a convalescent during July, 1919 overseeing the recovery of several patients.[9]

What is little known was the effect on the Aboriginal Community at this time as records are lacking both of infection rates and hospitalisation in Coffs Harbour. Although, Indigenous Australians, particularly in rural and remote areas, experience profound social disparity, including overcrowding, excess co-morbidity, poor access to health care, communication difficulties with health professionals, reduced access to pharmaceuticals, and institutionalised racism. During the 1918-1919 pandemic, mortality rates approaching 50% were reported in some Australian Indigenous communities, compared with the national rate of 0.3%.[10]

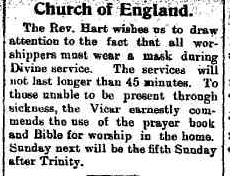

Even spiritual worship was not immune from the restrictions of the pandemic with a stern reminder of wearing masks for religious services and with an estimated finish time so the congregation would not be worried about spending so much in a public with so many parishioners.

Coffs Harbour and Dorrigo Advocate Saturday July 19, 1919, P.2. Retrieved from Trove.

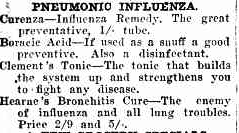

Local and regional businesses were keen to advocate all sorts of remedies to alleviate the symptoms of the Spanish Flu. Many people parted with their money judging by the volume and variety of so called “cures” appearing in the local newspapers. Below is a selection of the wide range of medicines available:

The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, 28 February 1919, P. 2. Retrieved from Trove.

The Tweed Daily Tuesday June 24, 1919, P.1. Retrieved from Trove.

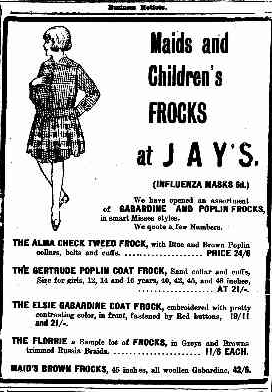

Nicely nestled in the Jay’s fashion advertisement of the latest fashionwear, was the sale of influenza masks at the fixed price of sixpence.

https://www.rahs.org.au/an-intimate-pandemic-the-community-impact-of-influenza-in-1919/

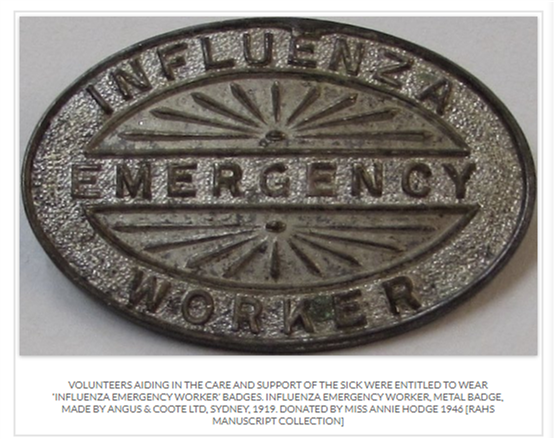

The role of volunteers during this period were essential for the control of the disease and although they were recognised in occasional columns in the Coffs Harbour Advocate, their role was quickly forgotten as the Federal Government’s action plan to rehabilitate Ex -Servicemen back into society through plans such as the Soldier Settlement Scheme had an immediate impact on the economy of Coffs Harbour. Yet there are small tangible reminders of the work completed by volunteers of the rarely seen Influenza Emergency Worker Badge. Coffs Harbour’ first recorded case was on April 1 and the official end of the disease was declared on July 6, 1919. Dorrigo was registered as the last town in New South Wales to record a Spanish Flu case on 27th September 1919.

The significance of the work against preventing this global pandemic through quarantining; extensive use of inoculations; wearing of masks and people adhering to restrictions of public association were successful in stopping the disease from being contagious in Coffs Harbour. The historical importance of this public health event has certainly been overshadowed by the end of World War One and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles by historians but the global response to the Spanish Flu does warrant more recognition for its significance in world history and in particular to those selfless men and women that cared for patients putting their own health at risk in doing their work.

Research by Charlie Bellemore, Coffs Harbour Regional Museum Volunteer.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus

[2] Joan Beaumont (2013) page 443 Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War

[3] Peter Rees (2014) page 295 Anzac Girls: The Extraordinary Story of Our World War One Nurses

[4] Susanna De Vires (2013) page 236 Australian Heroines of World War One

[5] Copy of letter 24/3/1919 from H S Robinson engine driver re irregularities in NSW Victoria border controls (prepared as Circular for Cabinet) [4/6247]

[7] Joan Beaumont (2013) page 443 Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War page 524

[8] Cowling, N (2012) Coffs Harbour Time Capsule Book 1847-2011 pages 146-147

[9] Yeates, Neil (1990) Coffs Harbour Story Volume 1 pre1880-1945 pages 104-106

[10] Massey, P. (2007) https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1179

References

Beaumont, J. (2013). Broken Nation Australians in the Great War. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Cowling, N (2012) Coffs Harbour Time Capsule Book 1847-2011 Office Choice. Coffs Harbour.

De Vires, S. (2013) Australian Heroines of World War One Brisbane. Pirgos Press

Rees, P. (2014) Anzac Girls: The Extraordinary Story of Our World War One Nurses Sydney. Allen and Unwin

Yeates, N. (1990). Coffs Harbour Story. Volume 1: pre1880-1945 Coffs Harbour: Banancoast Printers

Massey, P et al. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1179

Aldrich R, Zwi AB, Short S. Advance Australia Fair: social democratic and conservative politicians’ discourses concerning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their health 1972-2001. Social Science & Medicine 2007; 64: 125-137

https://www.rahs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Flu-Pandemic-proclamation-timeline-.pdf page41

https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus

Trove National Library of Australia

Letter 24/3/1919 from H S Robinson engine driver re irregularities in NSW Victoria border controls (prepared as Circular for Cabinet) [4/6247]

There is a record book in the museum archives which names the local people who caught the flu.

Thanks Terrie, Yes, Coffs was very fortunate in that pandemic to have a very low mortality rate.

It will be great to have the facility to link objects like the ‘Register of Infectious Diseases’ to our blogs soon.

Hi Terrie, is it located at the Coffs museum and is it accessible to the public?

Hi Stephanie, The Register of Infectious Diseases is not presently on display at the Museum, but has been partly digitised and will be able to be viewed on our new online service that will be available to the public soon. Thanks for your interest.